Adam Theisen leads ARM into a new era of data gathering and checks in with ASR along the way

Atmospheric scientist Adam Theisen, a data quality expert with a background in radar, grew up on a 200-acre dairy farm in central Minnesota. The homestead was a few miles from a town with barely 400 residents.

That’s about the same number of instruments he now keeps track of as instrument operations manager for the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

ARM has fixed and portable atmospheric observatories in climate-critical locations across the world and has been collecting and archiving data for close to 30 years.

Theisen works directly with the chairs of DOE’s Atmospheric System Research (ASR) working groups and national laboratory Science Focus Areas through his membership on the ARM-ASR Coordination Team.

One of the group’s biggest roles is to organize the agenda for the annual Joint ARM User Facility/ASR Principal Investigators Meeting, such as the one coming up on June 22-26, 2020.

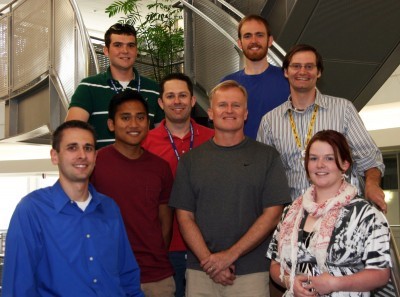

Theisen is based at Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago, where he manages the 70-plus ARM instrument mentors and their associates who assure the operational efficiency of all the instrument systems in ARM’s capabilities toolbox―computer-linked gear ranging from finger-size temperature probes to scanning radars the size of suburban houses.

A Wide Net of Mentors

Instrument mentors come from multiple DOE national laboratories and universities. Some are affiliated with other federal agencies, such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

They network with Theisen, others throughout ARM, and with instrument technicians at ARM atmospheric observatories to help others use the data more effectively. ARM has fixed sites in Oklahoma, Alaska, and the Azores as well as temporary deployments in Norway and on an icebreaker in the central Arctic.

Theisen took over as instrument operations manager in 2018 from now-retired ARM veteran Doug Sisterson, who said as he closed out his career, “I think of ARM as a factory and our product is data.”

Theisen was ideally suited to assume the role. He was operating radar systems in college while still a teenager. And for years he worked closely with Sisterson as a member ARM’s Data Quality Office based at the University of Oklahoma.

“The DQ Office,” as insiders call it, turns 20 years old this year. It’s ground zero for what Theisen calls “the first real assessment of ARM data quality.”

Lessons from Nature

Theisen is a native of tiny Upsala, Minnesota, where his high school graduating class was one of the largest ever at the time―about 42 students.

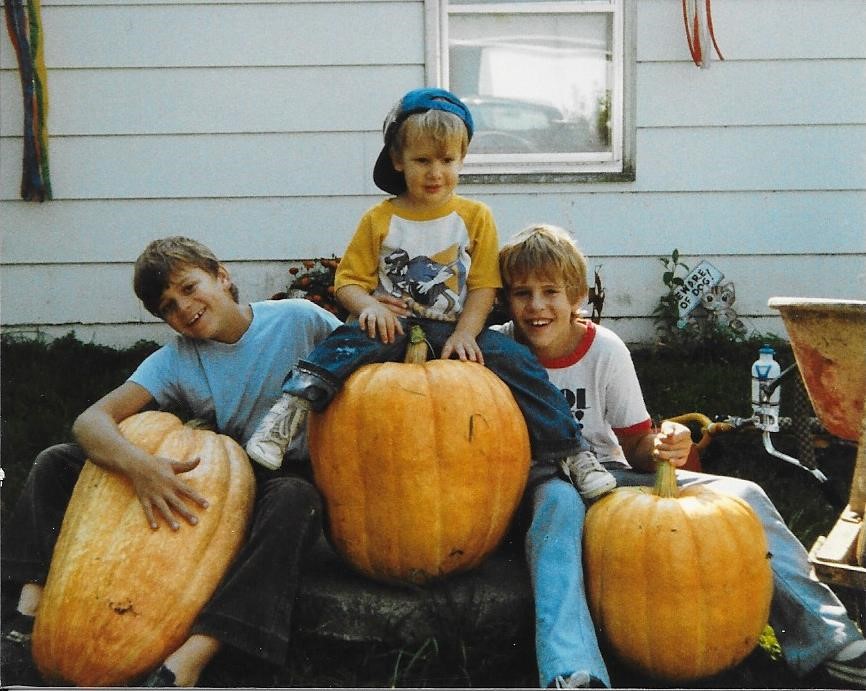

His father, Robert, studied marine biology and geology in college and instilled an observational rigor in his three sons. They were raised to see nature as both a wonder and the locus of facts.

“We were science-process-oriented on the farm,” at first with a geological spin, says Theisen. “We were always out in the fields looking at rocks.”

Meanwhile, both his father and his mother, Judy, “held us to high standards when it came to school,” he says.

At age 7, Theisen was standing on a stack of hay bales when the clouds above started to rotate.

“Rain chased me inside,” he says. But 20 minutes after the storm had passed, Theisen realized a tornado had struck within a mile of the family house.

“I was always interested in weather after that tornado experience,” says Theisen, who also admits to a boost from “Twister,” the 1996 big-screen disaster epic. Ryan, the oldest of the brothers―and now an accountant―took him to see it.

Radar Days

Propelled in part by the memory of that storm, “I knew at 14 I would be a meteorologist,” says Theisen.

By 2003, he was on his way to the University of North Dakota (B.S., 2007, M.S., 2009). The school had several attractions: a good meteorology program, a C-band radar on the roof of the department building, dramatic weather, and his brother Christopher, who by then was a meteorologist himself. (He taught Theisen two radar classes.)

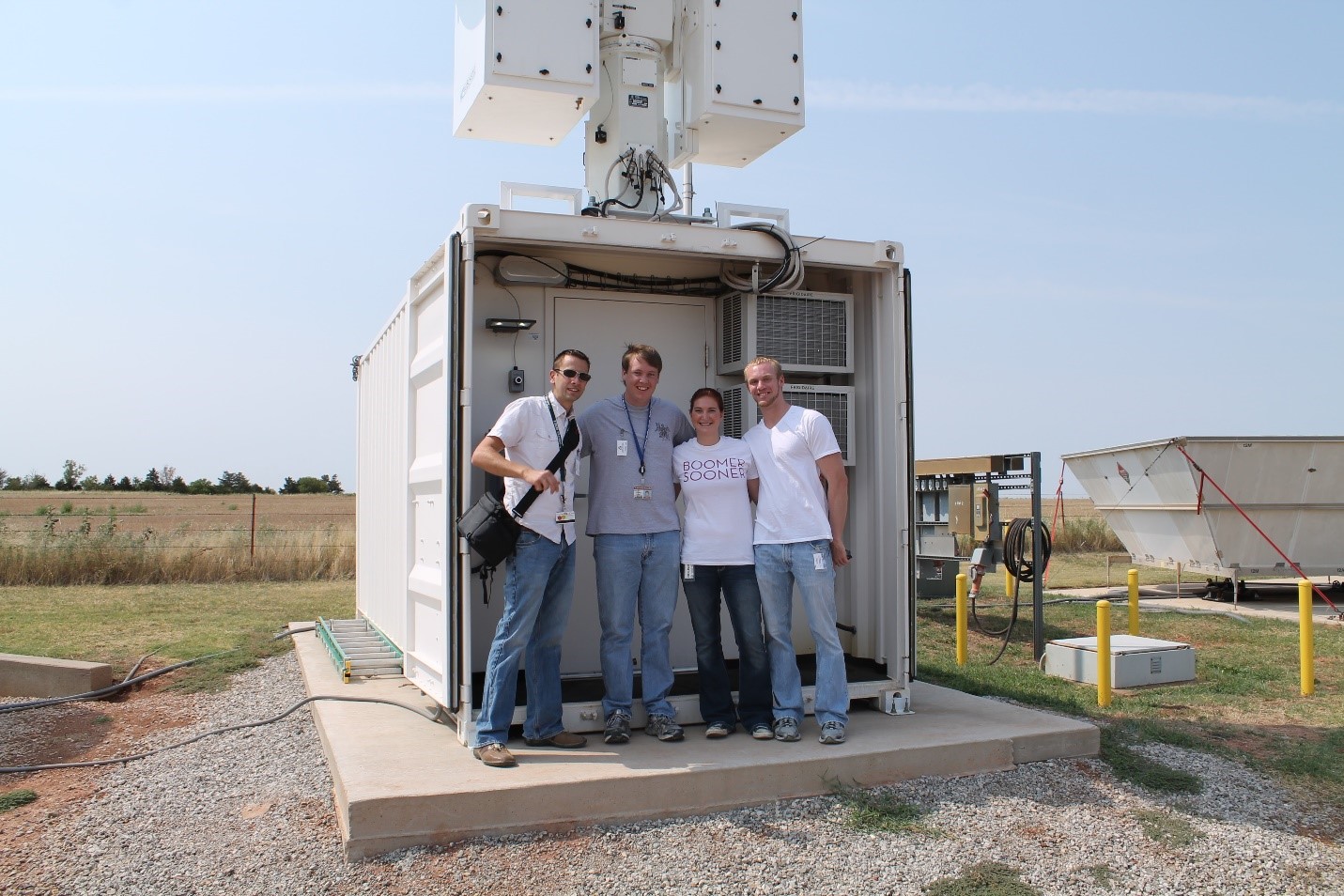

By his sophomore year, Theisen was part of a study on the climatology of storms in the area. The university’s old rooftop surveillance radar, WSR-74C, had been upgraded to a dual-polarized (polarimetric) system that transmits both horizontal and vertical radio wave pulses.

He ran sector scans of storm cells and before long, in 2006, was running the university’s rooftop radar for the first phase of a study of weather modification funded by North Dakota’s Atmospheric Resource Board. Theisen, among other tasks, radioed pilots on the best locations for cloud-seeding aircraft to light chemical flares at the base of clouds.

The Polarimetric Cloud Analysis and Seeding Test (POLCAST) went on to inspire short field campaigns in 2008, 2010, and 2012.

Adventures in Science

POLCAST gave Theisen a subject for his senior thesis, as well as a taste for field work.

In 2006, early in his junior year, he traveled to Senegal, in Africa. Theisen’s challenge was twofold: to help with rain gauges and radars during NASA’s African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analyses mission in Senegal, and to travel to Senegal. He had never been outside Minnesota and North Dakota.

“It was the furthest I had gone,” says Theisen.

Just after getting his bachelor’s degree in 2007, Theisen made his way to a summer internship at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia. He studied space weather―specifically how solar plasma discharges toward Earth affect the ionosphere and disrupt aviation communications.

The ionosphere, extending 60 kilometers to 1,000 kilometers (50 miles to 600 miles) above the Earth, is crowded with solar-charged particles called ions, which reflect radio waves.

During the Langley internship, Theisen met his future wife.

Ice Crystals, Rovers, and Satellites

In the fall of 2007, back in North Dakota for a master’s degree, Theisen investigated banded structures that appear on polarimetric radar data during snow events and how they correlate to ice crystal habit, a term for crystal type.

The research involved driving out into snowstorms to catch ice crystals on black fabric, then taking pictures of them in the shelter of the car’s trunk.

For nine months after graduating with his master’s degree, Theisen worked in West Virginia with Mountain State Information Systems Inc., then a NASA contractor vetting software for satellites and planetary rovers.

However, “just looking at code without being able to run it is not the most fun,” he says.

In March 2010, Theisen signed on with the DQ Office in Oklahoma. Among the satisfactions there was working with undergraduate student data analysts from the University of Oklahoma. In 2018, he helped two of them construct a low-cost weather station for about $300 in materials.

The low-tech, low-budget installation “did really well,” says Theisen, as a peer-reviewed paper now in review will show.

Beyond 2020

After eight years in Oklahoma, Theisen and his family made the move north to Illinois so he could manage ARM instrumentation and the staff who keep it running smoothly.

Sometime in 2020, he would like an ARM instrument dashboard in place that will consolidate, for internal staff, information from databases related to data quality, corrective maintenance, site operations, and other streams of as-yet-unconnected information. “I want to automate and simplify processes,” Theisen says of his plans for internal systems.

“Bringing all ARM’s instrument information together in one place would give us an overarching view of an instrument’s status that we do not currently have.”

In 2020 and beyond, he will also keep an eye on new instruments coming online at ARM, an “additive” process that Theisen says runs in parallel to the user facility’s expanding interest in data types.

For one, he points to an emerging emphasis on measuring precipitation inspired by the work of ARM instrument mentors Mary Jane Bartholomew, a geologist at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York and Matthew Sturm, a snow researcher at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Related investigations are unfolding at ARM’s North Slope of Alaska atmospheric observatory in the form of a new sonic snow-depth sensor, new bucket rain gauges, and a particle-measuring device for calculating the mass flux of blowing snow.

“New instruments up there will be very intriguing,” says Theisen, whose thoughts―of course―also turn to new instruments in the cloud-swept Azores, the Arctic, and elsewhere.

Building and Cultivating

At home, Theisen and his wife spent their time hiking, kayaking, and woodworking. That included several years of do-it-yourself efforts in their vintage house in Oklahoma.

“We had two weeks in our fully renovated house” before moving from Oklahoma to Illinois, he says.

There was also time for planting grapes, hops, blueberries, and more in raised garden beds; for home brewing (hence the hops); and for making crafts, including a two-story treehouse.

“I like building things,” says Theisen.

# # #This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, through the Biological and Environmental Research program as part of the Atmospheric System Research program.