An early-career scientist takes on a new committee and a project to improve models of marine clouds

Howard University atmospheric scientist Osinachi Ajoku was 5 years old when he traveled with his parents to their native Nigeria. He remembers seeing a giant mid-day sun, obscured in a haze of smoke, hanging in the sky like a blurry red disk.

It is a memory that seems prescient now.

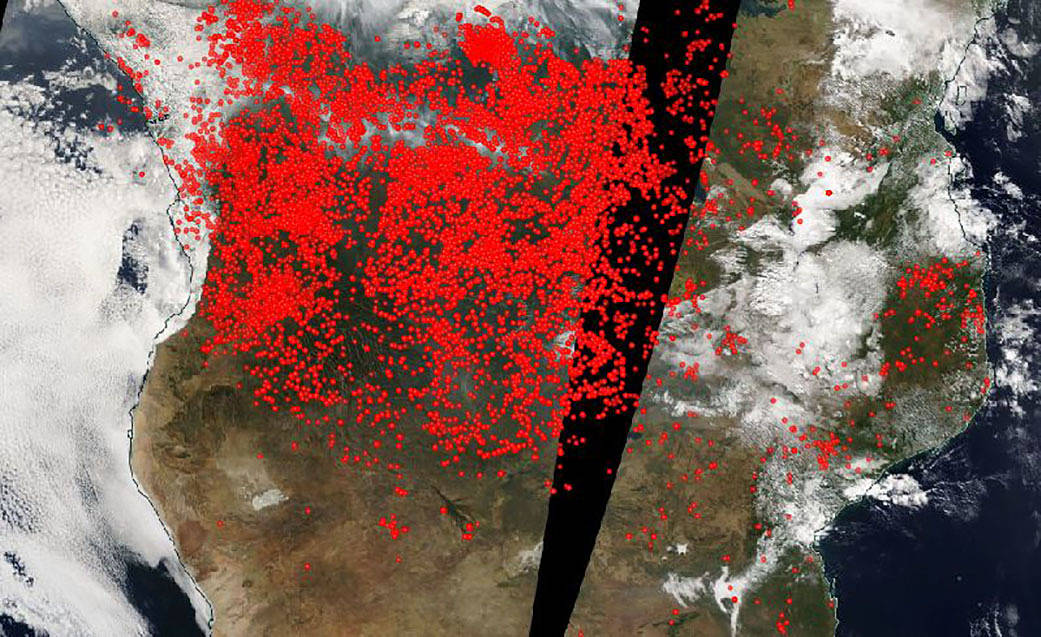

Ajoku is the principal investigator of a major project funded by the Atmospheric System Research (ASR) program at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). One of its science aims is to improve the accuracy of models simulating the impact of biomass burning in sub-Saharan Africa on vast decks of marine clouds to the west.

Joining him in the effort is Howard University co-PI Joseph Wilkins. Together, and with the help of a postdoctoral researcher in the fall of 2023, they will investigate how smoke affects cloud processes in the South Atlantic Ocean―how clouds form and transition from one type to the next.

“In the last three years, fires have gained a lot of headway in the media,” says Ajoku. “In Nigeria, I know fires are an every-year occurrence, and smoke pollution is a daily occurrence. But less is known about how smoke affects low marine clouds.”

Leaning on LASIC

Marine stratocumulus and cumulus clouds are more numerous than any other type, says Ajoku, and an ocean setting off the west coast of Africa “is the perfect testbed” to see how such clouds are affected by smoke.

The heart of that perfect testbed is a rich source of data on the marine clouds from Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM), a DOE user facility.

ARM operates six atmospheric observatories in climate-critical regions of the world. Three are in fixed locations and three are mobile. Some of ARM’s voluminous measurements record marine cloud processes.

Ajoku’s ASR project will rely on data from a 2016―2017 ARM field campaign called Layered Atlantic Smoke Interactions with Clouds (LASIC). The experiment included ground instruments from an ARM Mobile Facility set up on Ascension Island, a dot in the ocean 3,000 kilometers (1,865 miles) west of continental Africa in the South Atlantic Ocean.

Sweeping routinely above Ascension is a trade-wind regime of shallow cumulus clouds. Seasonally, these clouds carry a burden of smoke, above and below, from biomass burning.

LASIC data cover two biomass-burning seasons. The island-based campaign also had the advantage of overlapping with British and American aerial campaigns with roughly the same smoke-clouds mission.

To start, Ajoku and Wilkins are combing through satellite observations of stratocumulus clouds, looking for days with polluted and clean conditions.

“From these satellite snapshots,” says Ajoku, “we can start looking at the LASIC data, which are easily available.”

First, Seeing a Red Sun

During his first visit to Nigeria as a boy, “science was a foreign language,” says Ajoku, the son of a businessman and a nurse. “But what stood out were the images. Every time I went to Nigeria, I could not see the sun.”

Why that was true, he adds, “I never understood until I got to graduate school.”

Born in Los Angeles, Ajoku grew to love numbers, grew to love science, and in graduate school, fell in love with the puzzle of clouds and aerosols.

Beyond the blurry red sun of his first trip to Nigeria, other images of atmospheric phenomena turn up as memories for Ajoku.

Warning: His lifelong facility with numbers has given him a knack for remembering exact dates.

For instance, December 25, 1998 “was the first day of my life I saw hail falling on the ground,” says Ajoku, then age 9.

“Mentoring to me is a priority. You have to be the change you want to be.”

― Osinachi Ajoku

In 2003, at Susan Miller Dorsey High School in South Los Angeles, Ajoku joined a program that brought practicing architectural engineers into classrooms.

He helped build the blueprints for a rail line that opened 10 years later (“an amazing feeling”) between the University of Southern California and Santa Monica.

While still in high school, Ajoku was also an intern in the Fox Emerging Professionals Mentor Program, designed to offer clinical work, a free lunch, and a chance “to get inner city residents out of the neighborhood,” he says.

Most of the mentors were engineers.

Steering into Science

Propelled by such inspirations, Ajoku first studied biomedical engineering at California State University, Dominguez Hills (B.S. Earth Science, 2011), “but I saw early on I was not built for engineering.”

By February 2009, after a swerve into a B.A. program in geography, he was one day seized with the idea of getting a doctorate in hard science. Earth science, and its path to a B.S., rose as a choice in that direction, “in order to be a better (PhD) candidate,” says Ajoku.

It was the same year he became a vegan, a lifestyle choice that led him deeply into the science of nutrition, “looking at plants in nature,” and the work of German naturopath Arnold Ehret.

After graduating in 2011, Ajoku took a year off to work at Dominguez Hills with earth scientist Ashish Sinha, whose paleoclimate work involved studying stalagmite samples from caves in India. (In 2023, he coauthored a paper on paleoclimate changes in the Pacific Northwest, which came out of his time in the Sinha lab.)

“I am glad I caught some of that enthusiasm,” he says of that interlude, which also delivered further lessons on how to survive doctoral studies.

His introduction to aerosols and clouds came at the University of California, Riverside (M.S. Geoscience, 2014) during work on forcing agents in the tropics with climate change researcher Robert Allen.

“That’s my guy. He was there from Day One,” says Ajoku, who before his time at Riverside “had never heard of aerosols before, even in chemistry.”

On to a PhD

Starting from scratch, Ajoku quickly seized on the idea of aerosols as “the most important topic on the planet,” he says. “Every single cloud you see is composed of aerosols.”

Then came two big boosts: five years of funding for an advanced degree―three years from a National Science Foundation graduate research fellowship (he found out on April Fool’s Day 2014) and two from the University of California, San Diego (UCSD).

Doctoral studies also gave Ajoku a look at the wider world. He was among representatives from UCSD’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography at three annual Conference of the Parties (COP) events―in Morocco (2016), Germany (2017), and Poland (2018). “Parties” refers to signatories of the 1992 Kyoto Protocol.

Ajoku began his doctoral studies at Scripps (PhD 2020) with a July 2014 graduate division program on the dynamics of getting a doctorate―a fire hose of information, he remembers. “It was overwhelming, I’ll be totally honest.”

At Dominguez Hills, he says, there were a dozen geoscience undergraduates; at Riverside, there were 25 master’s students in his program; at Scripps, there were close to 300 doctoral students.

Ajoku met two mentors he leaned on throughout his PhD work: oceanographer Art Miller and climate scientist Joel Norris. Both were advisors for his dissertation, which was a warmup for the ASR project: an investigation of the impact of smoke aerosols on West African climate dynamics.

“More people that look like me are getting higher degrees,” says Ajoku about becoming a mentor himself. “That was a big motivation for me becoming part of the process.”

A Calling to Mentor

His academic career, just two years old, has given Ajoku the chance to share what he learned about the atmosphere, as well as the path that took him to the front of the classroom.

“Mentoring to me is a priority,” he says, including a climate lab page that blends aerosol science and student guidance. “You have to be the change you want to be.”

Another step in that direction is Ajoku’s newly elected post to ARM’s 13-member User Executive Committee (UEC), a group of advisors for the user facility from national laboratories, universities, and industry. He has the reins of a UEC subcommittee on undergraduate engagement and diversity, equity, and inclusion.

“It’s all about the research pipeline and strengthening that,” says Ajoku. “That means going back further and training undergraduates earlier about what graduate studies are like.”

Getting exposure to the rigors of graduate school, he adds, “starts with students as freshmen.”

It helps that in 2022 Ajoku received a two-year grant from DOE’s Research Development and Partnership Pilot to accelerate diversity among climate researchers.

Mentoring students “is the best part of my job,” he says. “It’s refreshing―it’s indescribable―to see someone else’s success.”

# # #

Author: Corydon Ireland, Staff Writer, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, through the Biological and Environmental Research program as part of the Atmospheric System Research program.