ASR-supported SCILLA experiment gathers data, flies to analysis

Dolphins and whales and sunfish, oh, my!

Researchers involved in the Southern California Interactions of Low cloud and Land Aerosol (SCILLA) experiment logged almost 90 hours in the air, observing cloud formation, pollution dynamics, and environmental interactions over land and water. As the scientists worked on board a low-flying Twin Otter research aircraft, they enjoyed views of marine animals frolicking in the waves of the Pacific Ocean below.

These scenes were part of the intensive operational period of SCILLA, a project jointly funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Atmospheric System Research (DOE ASR) program and the Office of Naval Research, in June 2023.

SCILLA was designed to complement the Eastern Pacific Cloud Aerosol Precipitation Experiment (EPCAPE), a field campaign conducted by DOE’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) user facility. EPCAPE is collecting data at two sites in La Jolla, California, from February 2023 through February 2024.

Scientists chose June as the month for the four-week SCILLA study because it is within the period of maximum frequency and extent of low cloud cover. This low cloud occurrence at the coast, known locally as “June Gloom,” made it the ideal time to gather below-, in-, and above-cloud data on air masses before they arrived at EPCAPE’s surface-based measurement sites. EPCAPE instruments are operating on the Ellen Browning Scripps Memorial Pier and Mount Soledad in La Jolla, on the north end of San Diego.

The Office of Naval Research funded the deployment of the Twin Otter, which is owned and operated by the Naval Postgraduate School (NPS). Mikael Witte, an assistant professor of meteorology at NPS, was the principal investigator for the flight deployment.

Don Collins, a professor of chemical and environmental engineering at the University of California, Riverside (UCR), is the lead principal investigator for the ASR portion of the project. Joining Collins are two co-principal investigators: Roya Bahreini, a professor of atmospheric science at UCR; and Andrew Metcalf, an associate professor of environmental engineering and earth sciences at Clemson University.

“We know we have a good data set. It’s often the things that you’re not anticipating, that you’re not initially planning to look at, where we see some really interesting features in the data.”

– Don Collins

Five graduate students—Minghao Han and Bradley Ries (UCR), Lt. Sierra Bollinger (NPS), Dongli Wang (Clemson), and Mason Leandro (University of California, Santa Cruz)—flew in at least one SCILLA research flight. They maintained and repaired instruments, performed calibrations, and monitored and analyzed data. These early career researchers will use the observations for the next few years in various projects.

Taking to the Skies

SCILLA researchers spread their flight hours over 21 flights, which took place almost daily during the intensive period. The few days off were mostly for required rest periods for the pilots and for standard aircraft maintenance.

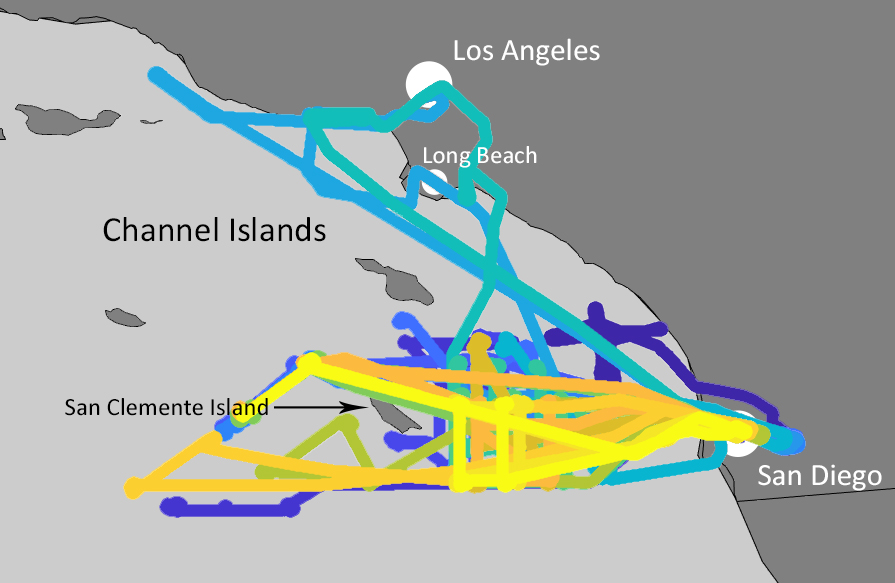

Because the Twin Otter is a Navy aircraft, the scientists could use military airspace and mostly avoid the highly congested airspace open to commercial traffic for the data collection. Most of the research flights covered an area west of San Diego near San Clemente Island. Occasionally, those areas were restricted. When that happened and on days with limited cloud cover, they took the opportunity to fly toward Los Angeles, in some cases flying over land in the Los Angeles-Long Beach area.

This aircraft-based project provided the opportunity to measure a range of conditions not always available at surface-based sites and offered regional context for EPCAPE. The research flights covered a large area, enabling the scientists to look at variability. They also provided a broader view of the spatial distribution of natural and pollutant aerosols and trace gases.

One objective of SCILLA is to better understand the pollution in the region that gets pushed offshore and is often transported toward San Diego. When they flew in the Los Angeles area, researchers got an initial view of the pollution particles and gases, and then captured them at multiple locations en route to San Diego. This helped them observe the formation and aging of particles as the polluted air got transported offshore and interacted with clean marine air masses.

“This region is really unique because you can find conditions ranging from pristine, with very low pollution background, all the way to very polluted, when you have a lot of outflow from the Los Angeles area that is being transported in that direction,” says Collins. “So, one of the advantages is that we can see the same clouds, the same environment under, in many cases, very different pollution conditions.”

Scientists measured aerosols, trace gases, water vapor isotopes, cloud droplets, thermodynamic properties, and radiation to try to better understand the influence of pollution, cloud microphysics, and cloud properties.

Next Steps for SCILLA data

While the intensive operational stage of SCILLA has ended, the three-year ASR project is far from over. The team is beginning to process the data now, and it hopes to have the first-order analysis of the data in the ARM Data Center by December.

Researchers headed into the campaign with an idea of what they would find—how varying aerosol concentrations affect a cloud, how aerosol properties change from day to day and by location, evidence of aerosol mixing, and more. While studying the data, they expect to find the unexpected.

“We know we have a good data set,” says Collins. “It’s often the things that you’re not anticipating, that you’re not initially planning to look at, where we see some really interesting features in the data.

“Until you start looking at graphs, not only of the measurements that you made, but the measurements you made combined with another data set or another few data sets, you start to see these features that sometimes at first don’t seem very interesting. Then when you look deeper, you really see something that is important in there.”

To some, that may be even more fun than spotting animals playing in the ocean.

# # #This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, through the Biological and Environmental Research program as part of the Atmospheric System Research program.