From a farm in India to deep into clouds

Some of us gaze at clouds. Some investigate them.

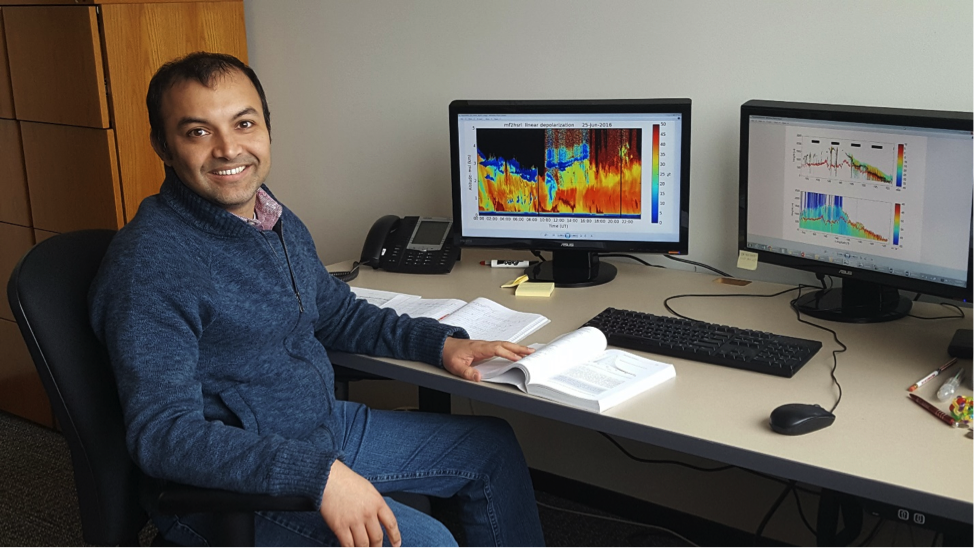

Virendra Prakash Ghate, an atmospheric scientist at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois, investigates the microphysics of low clouds, atmospheric radiation, and vertical velocity (mainly updrafts) within the atmosphere.

With clouds as a focus, his job, supported in part by Atmospheric System Research funding, is to consider our consequential sky and the forces within it that make weather and influence climate.

When Ghate was a boy in central India, the sky and clouds and the weather were consequential too—even existential. He watched his parents struggle to manage their maize and cotton farm near the city of Nagpur.

“We always paid attention to that,” said Ghate. “In an agrarian society even a few percentage points of change in rainfall has a big impact.”

Considering the frailty of farming life, when he was still a boy his parents encouraged him to have a good career, and early on he decided on mechanical engineering. One influence may have been his father’s job in a local tractor factory.

He and his brother (now an aerospace engineer with a doctorate from the University of Oxford) seized on the idea of doing well in school. Their parents—both college graduates with degrees in the arts—did not allow the boys to work on the farm and encouraged them to concentrate on studying and getting good careers.

With Clouds, an Awakening

In most lives, happy accidents happen. Ghate was an engineering undergraduate at Nagpur University when he won a chance to do a summer project at the prestigious Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. He set out to look into engine performance and biofuels. But at the last minute a key professor came down with the flu, so Ghate switched to an atmospheric science project. He liked it. “That was the topper for me, to take this seriously,” said Ghate, who went on to study both fields.

His undergraduate thesis took on a mechanical engineering topic, the design and fabrication of a vortex tube. But when it came time to apply for graduate schools in the United States, he sent out applications for both his fields of study.

Ghate accepted an offer from the University of Miami, dazzled by the strong program, the cloud science there, and the sheer adventure.

“I had never sat in an airplane,” he said of his trip to the United States, “never sat in an air conditioned room,” and until reaching Miami had never seen the ocean.

With plenty of air and sea travel along the way, he earned a master’s degree (2006) and then a Ph.D. (2009), both in meteorology. Ghate studied with now-emeritus professor Bruce. A. Albrecht, “the key figure in my career,” he said. “Where I am professionally, I give to him.”

Among other things, Albrecht was a principal investigator with ASR a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) program whose mission is to foster the study of key atmospheric processes. He was also involved in early planning for Southern Great Plains in Oklahoma, the first and largest observation site of the DOE’s Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Climate Research Facility.

Once Ghate arrived at the University of Miami, he faced two avenues of study: hurricanes and clouds. “I like clouds a lot more,” he said, admitting that today, once in a while, “I turn the (science) switch off and look at a cloud as just a cloud.” On airplane trips, Ghate takes photos of clouds “just because they are beautiful.”

Drizzle is beautiful too, especially when for your 2006 master’s thesis you publish new insights on characterizing the fine, light precipitation constantly falling “from big decks of clouds over oceans,” said Ghate. “Very little drizzle actually lands.” While at Miami, he went on several research cruises in the Pacific Ocean.

Ghate’s doctoral dissertation, in 2009, was on turbulence and mass transport in stratocumulus clouds—a set of issues that grips him to this day, even though “my research is getting broader and broader,” he said.

Present Pursuits

At the moment, in the lab, he is primarily working on the properties of boundary layer clouds, the low-lying formations that play a big role in the global energy budget. In particular, he is focused on how stratocumulus clouds are transformed into cumulus clouds.

Ghate is using data from the Marine ARM GPCI Investigation of Clouds (MAGIC), a 2012-2013 campaign funded by the ARM Facility, where the mission was to collect the climate observations needed to characterize atmospheric energy balance.

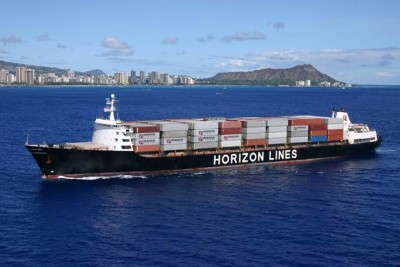

MAGIC turned parts of a working cargo ship into a marine observation platform for nearly a year of Pacific-traversing routes between Los Angeles and Honolulu. Portable instrumentation came from one of three portable platforms deployed by the ARM Facility. (Each ARM Mobile Facility, in this case the second AMF, is deployed for up to a year at a time around the world.) MAGIC yielded a large, rich, and rare data set on clouds, precipitation, aerosols, and radiation in a marine region of critical interest to global climate modelers.

Ghate is also working with data from a 2014 campaign funded by the National Science Foundation, Cloud Systems Evolution in the Trades (CSET). It used plane-based observation instruments to look at cloud, precipitation, wind, and aerosol regimes in the Northern Pacific.

During MAGIC he was not aboard the cargo ship Spirit to watch over instruments onboard. But during CSET, the now well-traveled Ghate flew in the research aircraft.

For experiences like this since starting his graduate studies—eye-opening travel in the Philippines, Panama, Chile, the Caribbean, and elsewhere—“I feel very grateful,” he said.

That gratitude is expressed, in part, by the effort Ghate puts into enhancing research within ASR, where he is co-chair of the Vertical Velocity Focus Group.

“He’s a go-getter,” said the other co-chair, Jennifer Comstock, an atmospheric scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. “If he says he is going to get something done, he does.”

All this—the role at ASR, the intense study of clouds, the expansive travel by ship and plane to advance science, and (more than anything, he said) the kindness of mentors—has given Ghate’s life an upward velocity of its own.

But his life always takes him back to Nagpur, and the steady aspirations that his parents embraced for their sons.

“This is how we grew up,” said Ghate, a sunny person in a world of clouds. “Do your best and look forward.”

# # #

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research as part of the Atmospheric System Research Program.

Scientist Profile: The Vertical Velocity of Virendra Ghate

Published: 27 March 2017